Hampshire County Mapping - a brief overview

16TH-17TH CENTURIES

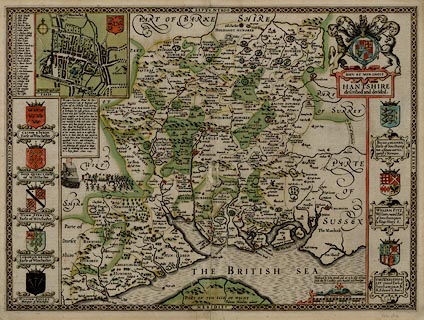

Christopher Saxton

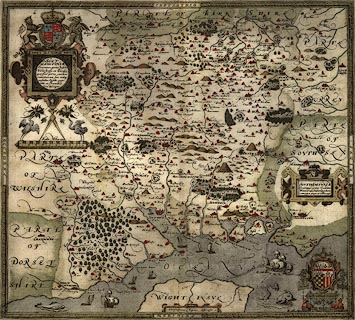

The first period of county maps begins with Christopher Saxton who surveyed the country in the 1570s, publishing a county atlas, the first ever such atlas:-Saxton, Christopher: 1579: Atlas of England and Wales

His survey methods are uncertain. He had access to good instruments and the latest knowledge about surveying, but the time he had to carry out the government sponsored survey was limited. The best guess seems to be that he worked by simple traverse, perhaps, only perhaps, just using a compass and way wiser, added to local knowledge. Christopher Saxton's map of Hampshire is dated 1575. Its scale is about 3 map miles to 1 inch; the map fits on a sheet of paper wxh = 50x44cm (20x17inches) which is folded in the atlas. Be wary of interpretting distances from his map; the mile used is not the modern statute mile but a customary measurement known as the Old English Mile, of uncertain standing and uncertain length. Christopher Saxton's map mile is about 1 1/4 statute miles.

His maps were made to satisfy the needs of an elizabethan government which, following the lead of Henry VIII, was continuing a process of modernising the administration of the country. William Cecil, Lord Burghley, Treasurer to Elizabeth I, used maps and his was the motivation behind Christopher Saxton's survey. Lord Burghley made use of the maps, annotating his own set with detail like the names of Justices of the Peace, the local agents for government.

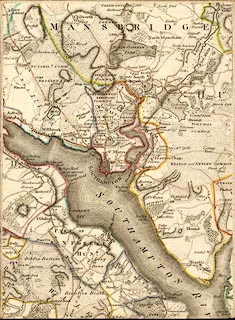

John Norden

Hampshire was surveyed again by John Norden in the 1590s, his manuscript map of Hampshire is dated 1595. The survey was part of a countrywide project, planned to be an atlas 'Speculum Britanniae' or 'Mirror of Britain' which failed. He surveyed only about 7 or 8 counties. His manuscript map of Hampshire still exists (British Library Add MSS 31.853) together with descriptive text and gazetteer of the county.A smaller version of the map was engraved and published in 1607 for:-

Camden, William: 1607 (6th edition, in Latin): Britannia

which includes extensive descriptive text on Hampshire. The map's scale is about 6 miles to 1 inch. An engraving of the original size map was made, probably soon after 1595, but no printed copy from the first state of the plate exists now (?). The copper plates survived and passed to a map publisher Peter Stent in the 1650s-60s, and then to John Overton from 1670. These publishers printed from the plate, each improving it a little with added engraving.

John Norden's map is not a copy of Christopher Saxton's. Comparisons that we have done show significant differences, and that later maps by Blaeu, Jansson, Morden match Norden's 1595 map rather than Saxton's. This can be seen by using the raw data files available on the sister website Old Hampshire Mapped. We do not know what surveying methods he used, but he did leave behind a textbook on surveying:-

Norden, John: 1607: Surveyor's Dialogue

John Norden comments on the map maker's problems; for one, the problem of access to the land being surveyed, for another the problem of jokingly or maliciously wrong information being provided by local sources. He also comments on accuracy, his own, or any map maker's:-

Because everye publique worke, is alwaies publiquely considered, and it is lawfull (I confesse) for all men, to utter their opinions therof freely as they finde it, and to call a fault a faulte. And because I cannot justifie all the Lineaments of so rude a body, I will saye with him that findes the fault (though in Art he cannot mend the same) Sir it is a fault and I will mend it if I can: But I have not yet seene the worke of the most absolute artist so perfect.This nicely and accurately sums up my attitude to my work with Hampshire Maps!

Greenvile Collins, who published a book of sea charts, 'Great Britain's Coasting Pilot', commented on John Norden's maps, reported by diarist John Evelyn, 2 February 1683:-

He [Greenvile Collins] affirmed, that of all the Mapps, put out since, there are none extant, so true as those of Jo: Norden, who gave us the first in Q: Eliz: time &c: all since erroneous

After Saxton and Norden

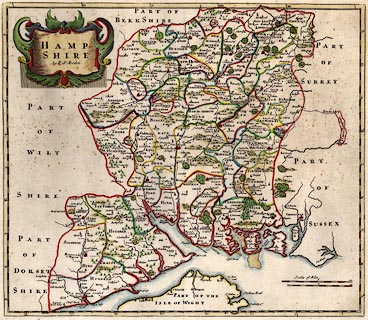

The maps that follow those of Christopher Saxton and John Norden through the 17th century copy from those two sources, and successively from one to another, and perhaps from some newer sources. There are some improvements, and there are errors of copying which are helped neither by unclear relationships between a symbol on the map and its label, nor by the language problems of dutch engravers working with english place names.A nice example of a copying error is seen on John Jansson's copying, 1646, of John Blaeu's map of 1645. On the earlier map the name 'Andover without Hundred' is engraved with 'without' decoratively out of line, in lowercase, and, as it happens, near a settlement symbol. On the later map the hundred is called 'Andover Hundred', duplicating the name of another hundred, and there is a new Hampshire village called 'Without'. How is a Dutchman to know this is not a perfectly ordinary place name in English?

A typical example of improvement is seen on Robert Morden's map of Hampshire, 1695, a hundred years after John Norden's which it copies to a large extent. The coast line is different, and more accurate; it is probably taken from a chart of The Solent in 'Great Britains Coasting Pilot' by Greenville Collins, 1693. And roads were added from the road survey by John Ogilby published in 1675.

Robert Morden's map was used in:-

Camden, Wiliam & Gibson, Edmund (translator): 1695 (in English): Britannia

John Ogilby

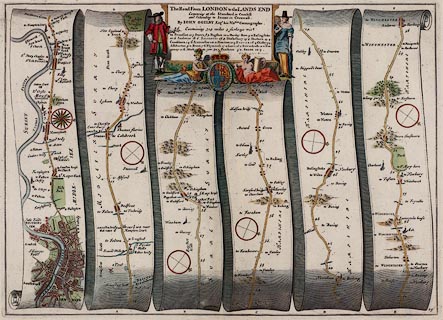

John Ogilby's survey of the roads of England and Wales in the 1670s is a different sort of mapping altogether. The printed maps are strip maps of the routes, the road is up the middle of a series of narrow 'scrolls' drawn on the sheet; little is shown of the surrounding countryside. 100 plates for 7519 miles of road were published in:-Ogilby, John: 1675: Britannia

10 of the plates concern Hampshire. The quality of this survey is excellent: matching John Ogilby's roads to modern days roads (for example the OS 1 to 25000 maps) you will be amazed at the goodness of fit. The strip maps are to scale about 1 mile to 1 inch; perhaps setting the standard that is still popular. His mile is 1760 yards, what is now a statute mile. Though, again beware, quoted distances to places off the route tend to be in customary miles. John Ogilby's survey methods involved the use of a waywiser to measure distances. One of the aims of the survey was to delineate the post roads for letters, a central government responsibility.

John Ogliby commented on maps available in the 1670s, that they were mainly versions of Christopher Saxton's:-

more and more vitiated since by Transcribers and Copiersand that the maps of the day were:-

Eminent for the Curious Performances of the Graver; their most Accurate Maps being but so many Guess-Plots.And still in the mid 18th century the Gentlemens Magazine, vol.17 p.406, 1747, could say:-

... nothing is easier than to copy former maps, and old descriptions of counties, in most of which are numberless errors

Other map makers of the 17th and early 18th century copied from map to map, claims of new and accurate surveys notwithstanding. John Speed, William and John Blaeu, John Jansson, Richard Blome, John Seller, Robert Morden, Alexander Hogg, Herman Moll, ... followed this way which was continued at least to John Harrison's map of 1788, which really ought to have been better done. John Ogilby's strip maps were copied as well, by John Senex, Thomas Gardner, Emanuel Bowen, Thomas Kitchin, Carington Bowles, ... most of them to a smaller scale, more convenient for the traveller's pocket.

John Speed was honest about his copying; a famous quote from him in the introduction to his atlas:-

Speed, John: 1611=1612: Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain: (London)

is:-

... I have put my sickle into other mens corne ...

John Speed did add a new element, street maps. Each county map has a town plan; the Hampshire map has Winchester, Southampton is on the Isle of Wight map. His atlas provides the first coherent set of town plans for the country, some of which, like Winchester, were made from his own survey.

Sometimes a new map is not copied from the old but uses the original printing plate, perhaps 'improved' by deletions and new engraving. An engraved copper printing plate has a long life; its cost was not small, it is an asset not to be wasted. Plates were sold from publisher to publisher to be reprinted even a century or more later. There is a version of Christopher Saxton's map of 1575 published by Philip Lea in 1689 in which coats of arms are altered and added, a street map of Winchester is added, roads are added, and many other alterations made to the original copper plate, many decades after the original was drawn. Although the pace of change was much slower long ago such a gap assumes there was none! This map is probably the first road map of the Hampshire (excluding the tiny playing card map by Robert Morden, 1676). It was still being published in 1772.

18TH CENTURY

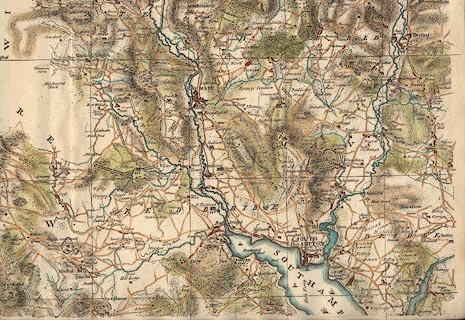

It is not until the middle of the 18th century that a completely new survey of Hampshire is made, carried out with a more scientific approach, and to a larger scale. This is motivated by the generally increasing awareness of the world and the increased ability to satisfy the appetite for knowledge; the two things feeding off each other. There was also the practical motivation of a premium, a prize, offered by the Society of Arts for better maps of counties.Isaac Taylor

In Hampshire the first 1 inch to 1 mile survey was made by Isaac Taylor in the 1750s, published in 1759. At this scale the county is about 135 x 120 cm (53x48inches) the map is printed on 6 sheets of paper. It was possible to paste the sheets together on linen to be rolled up or hung on a wall; or the sheets could be cut up, sectioned, so that when mounted they fold up neatly into a slip case. This last arrangement is easiest to handle but the gaps between the sections interfere with measurement.

Estate plans, at various large scales, have been drawn since much earlier times. These answer requirements of defining land ownership, enabling land management, and pride of the land owner. Some of the early textbooks on surveying, from the 16th century onwards, use estate surveying for their examples, for instance in:-

Leybourn, Wiliam: 1653: Compleat Surveyor, The

Isaac Taylor was an estate surveyor, working out of Ross on Wye, not London. His map does not have the best appearance, it is not so well engraved, but it is the earliest Hampshire map at a scale able to show lots of interesting detail. Beware that such detail might be incidential, it is usually not the result a careful survey of all that was there.

William Roy commented on Taylor's map alongside others, in a memoir to George III; they were:-

... sufficiently exact ... for common purposes ... extremely defective with respect to the topographical representation of the ground.

In the 18th century there was increasing interest in the accurate measurement of the earth's surface. Local astronomical measurements could fix positions accurately. At a national level the idea of an overall triangulation was growing, so that the mapping of the whole country would 'fit together'. The scheme does not bear fruit till after Isaac Taylor's survey; but he would have carried out a triangulation for his county map, a different approach from the road traverses used up to this time. Isaac Taylor's map failed to win a premium offered by the Society of Arts for 1 inch county maps.

Another change in society was the increasing awareness of the landscape by antiquarians, natural scientists and tourists. Isaac Taylor's own interests include antiquities, which are shown on his map. However, this is not entirely new; John Norden, for example, includes in his table of symbols a specific symbol for earthworks and marks some on his map.

Thomas Milne

A second survey for a map at 1 inch to 1 mile was made by Thomas Milne contracted by William Faden who published the map in 1791. William Faden had purchased the plates of Isaac Taylor's county maps, some of which he republished. He rejected the Hampshire survey, and instead had this new survey made. The resulting map is in 6 sheets and is a fascinating early picture of the county, including the new feature of canals which were part of a transport revolution in that century. It also gives names of many local landowners, a rich resource for us today, and includes notes on some land enclosures. Thomas Milne was an expert surveyor of his day; he contributed sections on surveying and plotting to a textbook:-

Adams, George: 1791: Geometrical and Graphical Essays

In 1793 the map was awarded a prize of fifty pounds from the Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce; the judges having inspected evidence of Thomas Milne's fieldwork, and asked the opinions of local magistrates. This premium had been advertised at intervals; in 1759, and in 1762:-

The Society proposes to give a Sum not exceeding one hundred Pounds, as a Gratuitity to any Person or Persons, who shall make an accurate Survey of any County upon the scale of one Inch to a Mile; the Sea Coasts of all Maritime Counties to be correctly laid down together with the Latitudes and Longitudes.

One inch maps, by the end of the 18th century, were an essential tool of administration much as they are today. This is a significant change in attitude from the early 16th century when the concept of a local map was still unfamiliar.

19TH CENTURY

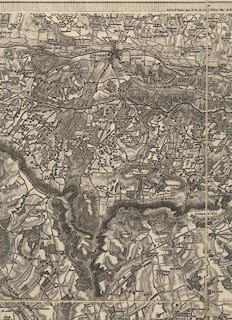

Ordnance Survey

The third era of mapping starts, at least emerges publicly, 1 January 1801 with the first map published by the Ordnance Survey. The OS was set up in the 1790s to map the whole of Great Britain.

The maps that include Hampshire were published in the 1810s. It is worth noticing that it is the country that is being surveyed not the county. Up till now maps were produced county by county; these are the major administrative units of the country. The OS maps in what is known as the Old Series of one inch maps break with that tradition. Other OS mapping, the County Series at 25 inches to 1 mile later in the century, return to it. Apart from thematic maps, tourism for instance, mapping today tends not to be closely focussed on county units.

The survey was as scientific as it could be. It was approached as a national project, with national resources. A triangulation of the whole country was set in place on which local surveying was based. An approachable description of the triangulation and survey is published by the OS in:-

Owen, Tim & Pilbeam, Elaine: 1992: Ordnance Survey, Map Makers to Britain since 1791: Ordnance Survey (Southampton, Hampshire):: ISBN 0 319 00498 8 (pbk)

The Ordnance Survey continues to supply us with 'one inch' maps. The series has gone through several editions, each having major changes of style; colour is introduced, a National Grid Reference system is applied, and lastly the scale rationalised from the 1 to 63360, 1 inch to 1 mile of the Seventh Series, to 1 to 625000 for the Landranger maps.

Charles and John Greenwood 1826

An independent survey of Hampshire was made, as part of a national series, by Charles and John Greenwood in the 1820s. They published a 1 inch to 1 mile map in 1826, in 6 sheets. Like Isaac Taylor's map the sheets might have been purchased singly, mounted on rollers, or sectioned for folding, mounted, in a slip case. The survey is not utterly independent making use of the triangulation made by the Ordnance Survey, and copying from the Ordnance Survey's maps covering the county, published in the 1810s. A number of place names are corrected, and hundred and parish boundaries added. In other parts of the country the Greenwoods did more of their own surveying.

There was an initiative in the 1820s to map Hampshire at an even larger scale, about 5 inches to 1 mile. This is the Great Map of Hampshire proposed and begun by Nathaniel Lipscomb Kentish. As far as is known he published only the prospectus with an index map (no copy yet found) and one lithograph sheet, an area south of Winchester. The project was given up in 1824, Nathaniel Kentish:-

... having too late found his gigantic undertaking to be impracticable, ...His work was not all lost; he is credited on one of the 1826 editions of the map by Charles and John Greenwood:-

and N. L. KENTISH.appearing coyly in the title engraving.

From the early 19th century onwards in the main the OS are the surveyors for maps. Many maps published were and still are reduced or revised from the Ordnance Survey. The history of map making is no longer county focussed; and its development is the general national and international development of surveying, sensing and mapping. However there continue to be many county maps published, showing in particular the development of railways, but also turnpikes, telegraphs, electoral divisions, geology, and various ways of representing relief. But there are so many from the later 19th century and beyond that this checklist can make no pretence to be 'complete'.

CHARTS

Hampshire is a coastal county, and moreover a county that hosts the Royal Navy at Portsmouth. Coastal defence is a particular concern. These notes are not primarily concerned with sea charts, but some items in the Map Collection deserve notice:-chart of the Sea Coast of England in the sea atlas, Mariners Mirrour by Lucas Waghenaer, in English 1588, earlier in Dutch 1583.

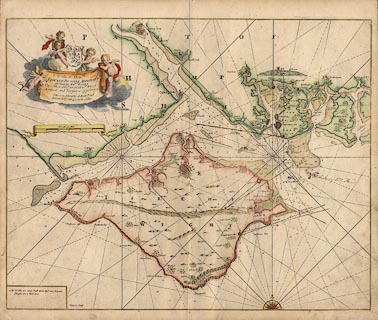

chart of The Solent in Great Britains Coasting Pilot by Greenvile Collins, published 1693.

charts of the coast by Murdoch Mackenzie jnr 1780s.

ENGLAND, WORLD

Hampshire is in England and maps of the country show the county. Some World maps show recognisable features in the county. No thorough search has been made to see 'Hampshire' on all such maps, but they should not be forgotten when studying the county. Many of the bigger area maps are worth notice, the selection here partly reflects what happens to be in the Map Collection or has passed through our hands as an enquiry:-on 16th century 'Ptolemy' maps of Great Britain it usually possible to find Venta - Winchester and the area of the Belgae

the Gough Map of England, about 1360, has about a dozen Hampshire places and two routes drawn across the county.

George Lily's map of the British Isles 1546 has Portsmouth Harbour, Winchester, Southampton and half a dozen other Hampshire towns.

Humphrey Lloyd's map of England published by Abraham Ortelius 1573 has about three dozen Hampshire places.

It is worth noting that research into very early maps is severely compromised by lack of access to sources. The maps are scattered over the World. Even those in the British Library, London, were not conveniently or affordably reached from where I lived 100 miles away. Working from reproductions printed in books is usually impossible; the illustrations are never readable and seem to have been offered merely as decoration.

At slightly later periods there are many maps of the British Isles, each showing Hampshire in more or less detail. The checklist includes a sample of such maps, generally because they have been acquired for the HMCMS Map Collection.

REFERENCES

Various books are suggested under particular map makers. The following works have interesting comments about county mapping:-Harley, J B: 1965: Re-mapping of England, The: Imago Mundi: vol.19: pp.56-67

Harley, J B & Dunning, R W: 1981: Somerset Maps (introduction): Somerset record Socisety: vol.76: ISBN 0 901732 24 9

Laxton, Paul: : 250 Years of Map Making in the County of Hampshire 1575 to 1826 (introduction): Margary, Henry

Penfold, Alastair: : Introduction to the Printed Maps of Hampshire: Hampshire CC Museums Service